Determining the Field Metabolic Rate of Marine Predators

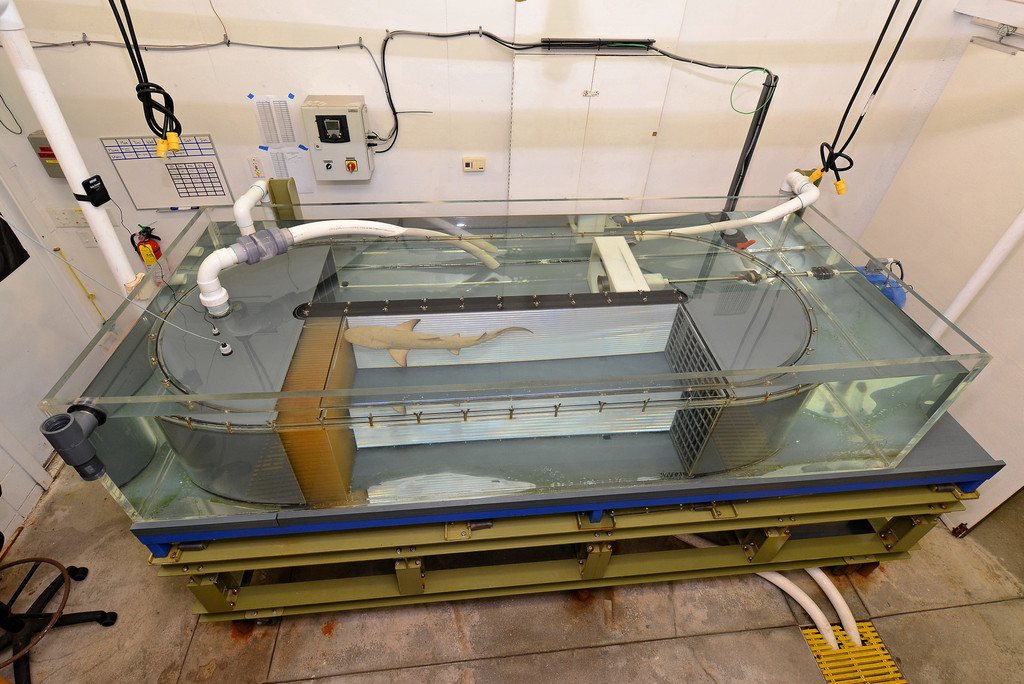

We are measuring the metabolic rates of coastal sharks by swimming them in a “shark treadmill” called a respirometer. Here, their oxygen consumption can be recorded and correlated to their swimming behavior, as measured by an accelerometer tag. The tags can then be used to quantify the metabolic rate of sharks in the wild so we know how much energy they are using and how much food they must consume to replace that energy. This study is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Discard Mortality of Sharks Caught on Commercial Longlines

In order to properly manage shark populations it is important to understand the total mortality caused by fishing. Sharks are often caught as bycatch or discarded at sea because they are prohibited species, but how many of these caught and released sharks survive? We are answering this question by measuring blood stress indicators in captured sharks and following the animal’s outcome (survived or not) after release using accelerometer tags. We are focusing primarily on sandbar and blacktip sharks, but also tiger, bull, spinner and other shark species. This study is funded by NOAA/National Marine Fisheries Service and the Waitt Foundation.

Behavior and Energetics of Female Loggerhead Sea Turtles

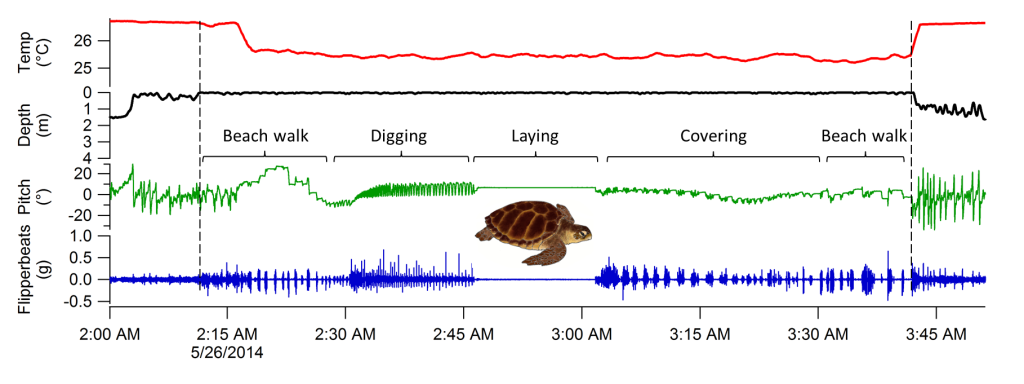

Female loggerhead sea turtles will crawl up on beaches to dig a nest and lay eggs repeatedly throughout their summer nesting season. One curious behavior often observed is the “false crawl” where a turtle will crawl up the beach and may even dig a full nest before abandoning it without laying eggs, possibly because it is disturbed by lights or other human-related activities. We are working with USGS collaborators to attach multi-sensor tags to these animals that can detect both nesting and false crawl events over the course of a nesting period. We also monitor the success of the nests that these animals lay, and we are trying to determine whether multiple false crawls (which are presumed to be energetically costly) lead to a reduction in the number of eggs a female will lay in a season. This study is funded in part by a Sea Turtle License Plate Grant from the Sea Turtle Conservancy of Florida.

Detecting Mating and Other Unique Behaviors in Sharks

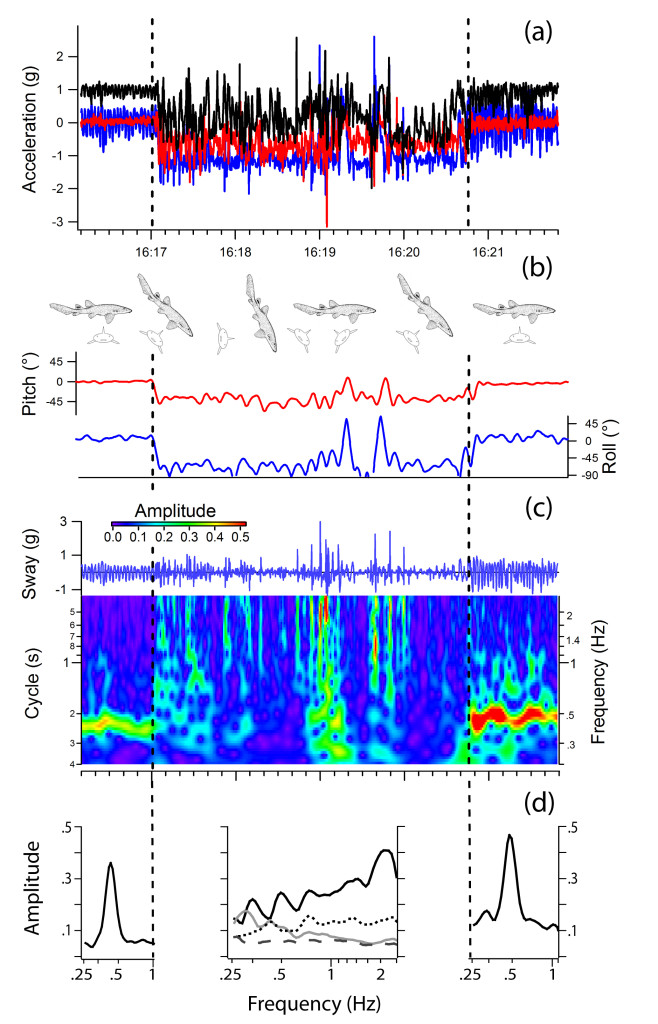

We have published the only study to use multi-sensor tags to detect mating behavior in sharks, with tag data validated by direct observation. Because mating behavior produces unique characteristics in acceleration and depth data, we are using our catalogue of data signatures from shark mating events to develop algorithms that can be used for onboard data processing and event detection in the next generation of wildlife tags. These tags would stay on animals for months to years using little power or memory until they detect and transmit the occurrence of an event. This study has been founded by the Waitt Foundation and National Geographic Society.

The Effects of Catch and Release Fishing on Blacktip Sharks

Many fishermen now practice catch and release fishing for sharks instead of keeping them for food or trophies. But do all of the sharks caught and released actually survived? This is a difficult question to answer and has important management implications. We are working with recreational fishermen to find out what happens to blacktip sharks after they are caught on rod and reel and released. We do this by drawing blood from the sharks to look at several measures of stress, and by tagging them with an accelerometer to record their fine-scale swimming movements and find out whether they survive. This study is funded by NOAA/National Marine Fisheries Service.

Fine-scale Activity Patterns of Juvenile Green Sea Turtles

We are working with colleagues at the USGS to measure the fine-scale behavior and energetics of juvenile green sea turtles in a shallow foraging ground in Dry Tortugas, FL. We are quantifying how much time they spend foraging, resting, diving, etc., and examining the energetic constraints that are driving their behavior. This study is funded in part by a Sea Turtle License Plate Grant from the Sea Turtle Conservancy of Florida.

Fine-scale Behavior and Movements of White Sharks

Since 2012, we have been collaborating with scientists at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (MDMF), the non-profit research group Ocearch, and several other institutions in a multi-disciplinary and comprehensive study of white sharks off the East Coast of the United States. Data from our acceleration data loggers have thus far shown that these animals appear to recover very quickly (within 3-4 hours) after the capture and tagging process, and that some individuals engage in repetitive diving behavior marked by swimming up toward the surface and “gliding” down to the bottom without beating their tails. Long-term movements from satellite tag data being analyzed by MDMF scientists have shown extraordinary coastal and trans-oceanic movements, and can be tracked at Ocearch.org. The fine-scale behavior component of the study is funded by the Waitt Foundation and OCEARCH.

Jumping Behavior in Gulf Sturgeon in the Suwannee River, Florida

Gulf sturgeon come into the Suwannee and other rivers in North Florida during the summer months to spawn, and they return to the Gulf of Mexico during winter months. While in the Suwannee, these animals often aggregate in certain parts of the river and can be seen jumping out of the water quite frequently, at times up to one jump every eight seconds. This behavior has proven to be extremely dangerous to boaters using the river who collide with these heavy-bodied, well-armored fish. We are collaborating with scientists at the USGS to attach accelerometer tags to these animals that monitor their depth, temperature, and swimming behavior in an effort to understand exactly when, how and why they jump out of the water.

Activity Patterns of Invasive Burmese Pythons in the Everglades

Burmese pythons are an invasive species to the Florida Everglades, introduced over a period of many years through the exotic pet trade. They are now a breeding population that is decimating native populations of small mammals, birds, and other species. These animals are incredibly difficult to find and extract from the wild, but knowing when they are most likely to be on the move increases the likelihood of capturing them. We are working with collaborators at the USGS to track the snakes activities and body temperature using acceleration data loggers.